I have watched academic integrity policies evolve for years, and I will say this plainly. In the age of AI, trying to catch students using tools is a losing battle. I have seen detection software fail, policies confuse students, and honest learners punished for unclear rules. What works is not surveillance. What works is clarity, design, and trust.

When AI entered classrooms, many institutions reacted with fear. Ban it. Block it. Police it. But students did not stop using AI. They simply stopped talking about it. That silence is where misconduct grows. I have learned, through practice and discussion with educators, that integrity survives when we shift the focus from hiding AI use to documenting and reflecting on it.

Everything starts with clarity.

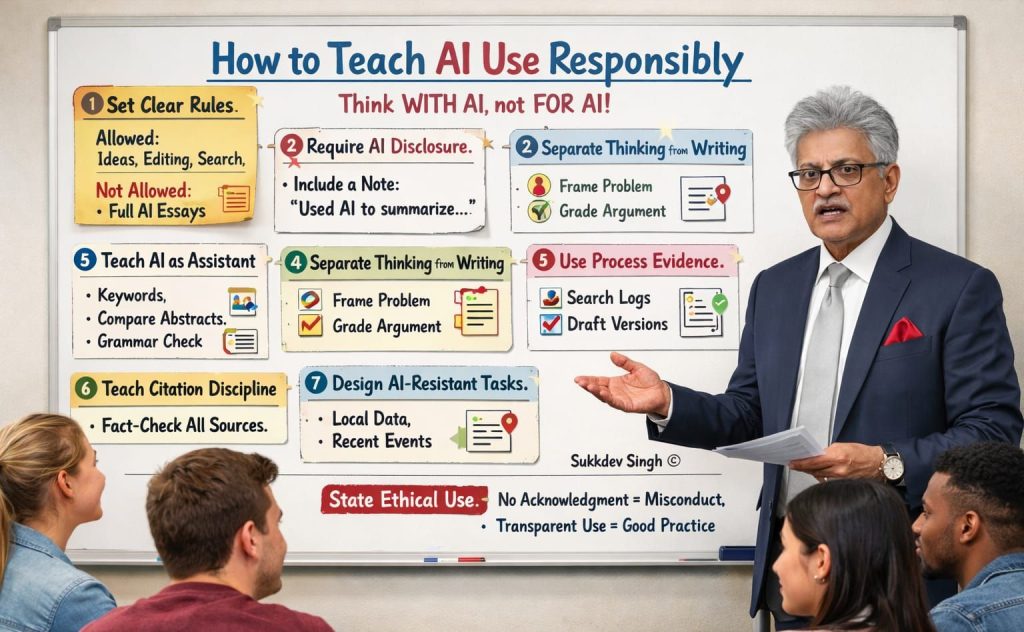

The first responsibility lies with the syllabus. If AI rules are vague, students will interpret them in their favour. If they are invisible, students will ignore them. You need to make AI use explicit and visible. State clearly what is acceptable and what crosses the line. Idea generation, refining search terms, improving language, these are legitimate supports. Submitting AI-generated analysis as original thinking is not. Ambiguity is not neutral. It creates ethical grey zones where students stumble.

Next comes disclosure. I strongly believe AI use should be declared, not denied. A short note is enough. Something as simple as, “Used AI to summarise five abstracts and rewrote the final synthesis myself.” This mirrors what journals and funding agencies are beginning to demand. Transparency normalises ethical behaviour. It also removes the fear students feel when they use tools quietly and wonder if they will be accused later.

We must also teach students what AI is for. AI is a research assistant, not a writer. I always emphasise this distinction. Show students how to use AI to generate keywords from a research question. Show them how to compare abstracts across databases. Ask AI to surface counterarguments to a draft thesis. Use it to check clarity and grammar at the final stage. These uses strengthen thinking rather than replace it. When students see AI as support, not substitution, integrity follows naturally.

Assessment design matters even more. Thinking and writing must be separated. If language quality carries most of the marks, AI will dominate. Instead, grade problem framing, source selection, and argument structure independently from expression. AI still struggles with original reasoning and contextual judgement. By valuing these elements, you protect academic integrity without banning tools outright.

Process-based assessment is another quiet but powerful shift. Ask for search logs, prompt histories, draft versions, and short reflections. Ask students where AI helped and where it failed. This changes what you assess. You stop judging only the final output and start evaluating learning itself. From my experience, students become more reflective and more honest when they know their process matters.

Citation discipline must be taught early and repeatedly. AI can fabricate references, blend sources, and paraphrase without attribution. Students often trust it blindly. They should not. Train them to verify every citation using Google Scholar or Scopus. Make verification a habit, not a warning. Once students understand how easily errors slip in, they become more cautious and responsible.

Assignment design is the final safeguard. Generic prompts invite generic AI responses. Local data, recent events, personal reflection linked to theory, or comparison of two specific papers make shallow AI output obvious. These designs do not fight AI. They outgrow it.

And then, you must say this clearly and consistently. Using AI without acknowledgement is misconduct. Using AI transparently and critically is a scholarly practice. Students understand rules when we speak plainly and apply them consistently.

The goal is simple. Students should learn how to think with AI, not outsource thinking to it. If we design teaching and assessment with this goal in mind, integrity does not weaken. It matures.